doi: 10.56294/ere202212

ORIGINAL

Productive organization in MAPU de Chiclayo: A proposal for its socioeconomic development

Hodología productiva en MAPU de Chiclayo: Una propuesta para su desarrollo socioeconómico

Jorge

Carlos Carrasco Aparicio1 ![]() *,

Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén1

*,

Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén1

![]() *,

Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo2

*,

Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo2

![]() *

*

1Universidad San Martin de Porres, Filial Norte. Chiclayo, Perú.

2Universidad Católica Santo Toribio, Mogrovejo. Chiclayo, Perú.

Cite as: Carrasco Aparicio JC, Gamarra Sampén MA, Martín Vargas Chozo OV. Productive organization in MAPU de Chiclayo: A proposal for its socioeconomic development. Environmental Research and Ecotoxicity. 2022; 1:12. https://doi.org/10.56294/ere202212

Submitted: 21-04-2022 Revised: 08-07-2022 Accepted: 11-10-2022 Published: 12-10-2022

Editor: Prof.

Dr. William Castillo-González ![]()

Corresponding Author: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio *

ABSTRACT

This research focuses on the Urban Pre-Hispanic Archaeological Monuments (MAPUs) in the district of Chiclayo, Peru, which face problems of degradation and loss of their social, cultural and economic function due to the expansion and saturation of urban occupation. Inspired by the Inca road Qapaq Ñam, hodology is used as an approach to study the MAPUs and their influence on human behavior. Through the use of fractal geometrization and triangulations, traditional spaces are connected with current opportunities for socioeconomic, cultural and ecological development. The project strategy aims to transform inactive MAPUs into active hodological spaces. To achieve this, it is proposed to enhance current uses, creating mixed-use and specific-use corridors that promote continuity and diversity in the use of the streets, taking advantage of existing infrastructure and productive resources. A pilot project is being implemented in the César Vallejo MAPU, reinventing itself as a strategic point of transformation for the city through its temporary collective use, allowing the management of locally rooted projects with a global vision. Chiclayo requires open strategies instead of massive urban projects, promoting a productive landscape, in uninhabited territories, capable of generating energy, food, goods and knowledge on multiple scales. The MAPUs thus become active public spaces that improve social relations and merge agriculture, architecture and infrastructure, with community participation and programmatic mutations. This redefinition seeks to establish a productive identity in natural-artificial groupings and to adopt urban-rural approaches for sustainable and equitable development in the region.

Keywords: Pre-Hispanic Archaeological Monuments (Maps); Productive History; Uninhabited Territory; Productive Landscape.

RESUMEN

Esta investigación se enfoca en los Monumentos Arqueológicos Prehispánicos Urbanos (MAPUs) en el distrito de Chiclayo, Perú, los cuales enfrentan problemas de degradación y pérdida de su función social, cultural y económica debido a la expansión y saturación de la ocupación urbana. Con la inspiración del camino inca Qapaq Ñam, se utiliza la hodología como enfoque para estudiar los MAPUs y su influencia en el comportamiento humano. Mediante el uso de geometrización fractal y triangulaciones, se conectan espacios tradicionales con oportunidades actuales de desarrollo socioeconómico, cultural y ecológico. La estrategia proyectual tiene como objetivo transformar los MAPUs inactivos en espacios hodológicos activos. Para lograrlo, se propone potenciar los usos actuales, creando corredores de uso mixto y específico que fomenten la continuidad y diversidad en el uso de las calles, aprovechando las infraestructuras existentes y recursos productivos. Un proyecto piloto se implementa en el MAPU César Vallejo, reinventándose como un punto estratégico de transformación para la ciudad a través de su uso colectivo temporal, permitiendo gestionar proyectos de arraigo local con visión global. Chiclayo requiere estrategias abiertas en lugar de proyectos urbanos masivos, promoviendo un paisaje productivo, en territorios inhabitados, capaz de generar energía, alimentos, bienes y conocimiento en múltiples escalas. Los MAPUs se convierten así en espacios públicos activos que mejoran las relaciones sociales y fusionan agricultura, arquitectura e infraestructura, con la participación comunitaria y mutaciones programáticas. Esta redefinición busca establecer una identidad productiva en agrupamientos naturales-artificiales y adoptar enfoques urbano-rurales para un desarrollo sostenible y equitativo en la región.

Palabras clave: Monumentos Arqueológicos Prehispánicos (Maps); Hodología Productiva; Territorio Inhabitado; Paisaje Productivo.

INTRODUCTION

In the context of our research, we refer to Careri F(1) Walkscapes to establish a connection that transcends both time and space. This journey takes us from the ancient footprints left by the Muchik culture, a pre-Hispanic civilization in northern Peru, to the current socioeconomic and urban challenges facing the city of Chiclayo, located in the fertile Chancay-Lambayeque Valley. The research seeks not only to understand the history and culture of this region but also to identify innovative opportunities for its sustainable development.

The starting point is a Muchik iconography by Jurgen Golte, which reveals a deep connection between cosmic, marine, and terrestrial balances. The Chancay-Lambayeque Valleys and other productive areas along the northern coast of Peru served as an ecological setting for ancient civilizations that colonized and shaped the territory. These civilizations left a legacy of landmarks and infrastructure that supported the productivity of the valleys and integrated harmoniously with the environment, recognized today as Pre-Hispanic Archaeological Monuments (Huacas). These structures, inherited from ancient cultures, have survived, adapting to different historical layers and urban uses. However, some huacas face extinction in areas of informal growth, while others, although “protected,” are isolated by walls and do not participate in city life.

One of the first methodologies generated as neural networks in the Tahuantinsuyo were the lines now recognized as the Qapaq Ñan, where the lines between the coast and the mountains interwove the valley and connected points of interest throughout South America. In the act of abstraction, we take this ancient anthropized urban fabric to a new dimension, using fractal geometry and triangulations to explore how pre-Hispanic roads connect with potential areas of human and urban development today.

By looking back in time and adopting a multi-scale perspective, we appreciate the richness of the ancient urban “quipus” and recognize the evolution of metropolitan areas, which have left behind monochromatic functionality and fragmented the cultivation areas throughout the territory. This change is evident in the current dynamics of Chiclayo, a city in the heart of the Chancay-Lambayeque Valley, which is the primary focus of this research.

However, this journey is not limited to a historical and archaeological study. The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken urban life as we knew it, intensifying pre-existing pathologies in the pre-pandemic “normality.” Over the decades, Latin American cities have witnessed urban mutations and paradoxical arrangements that respond to the changing needs of society. However, this evolution has led to dispersed urban growth that has not diminished in its desire to erase every historical trace through a superimposition of reactive functional layers as it adapts to the needs of each era; however, it often invades or nullifies public space, overlooking its essential function as a generator of social interactions and opportunities for biodiversity. Instead of being articulated meeting places, public spaces have become scenes of socioeconomic inequality and isolation.

Half a century after the reflections of French philosopher Lefebvre H(2), who advocated for a dignified city that recovers its recreational and social use, many Latin American cities, including Chiclayo, find themselves trapped in urban obsolescence. The lack of territorial planning and the adoption of functionalist models have fragmented urban life and undermined the essential function of MAPUs (Pre-Hispanic Urban Archaeological Monuments) as generators of public space and community activities.

The city of Chiclayo, our field of study, has seen its functions blurred, allowing the proliferation of what anthropologist Augé(3) described as “non-places”, anonymous areas that can accommodate many people but lack meaningful social interactions. This transformation has been exacerbated by the lack of interest of local authorities in the conservation and creation of new public spaces, which has led to the abandonment of these places by humans and non-humans alike, who now seek refuge on private property.

Past urban interventions based on functionalist models have proven ineffective in Latin American cities. They were often planned from the top down without considering the population's participation or long-term sustainability. As a result, MAPUs often function as barriers rather than points of integration within the community. According to the Stockholm Resilience Center,(4) it is essential to rethink how we inhabit urban spaces and do so in a participatory manner, involving the local population in planning and decision-making.

In Chiclayo, the degraded and/or abandoned state of the MAPUs is seen as an opportunity. Through an approach that values community knowledge and resources, local people can be empowered and given an active role in transforming their urban environment. Chiclayo, with a population of nearly half a million and constantly growing economic and cultural potential, can benefit significantly from greater citizen participation and more inclusive urban development plans.

The research seeks to reestablish the connection between the Huaca, the neighborhood, and the city, fostering a sense of belonging and opening the door to meaningful dialogue between the archaeological heritage and the contemporary community.

This multidimensional journey takes us through time and space, from ancient pre-Hispanic civilizations to the contemporary city. We explore how the past and present intertwine at each step and offer opportunities for a more sustainable and resilient future. This research is a call to action, an invitation to reimagine and revitalize our cities, taking their history as a starting point and building an urban environment relevant to the community.

METHOD

The research has focused on an interdisciplinary methodology that integrates various tools to understand and revitalize Pre-Hispanic Urban Archaeological Monuments (MAPUs) in Chiclayo, with a special focus on the hodological approach, fractal geometrization techniques, spatial triangulations, project strategy, and a pilot project in the César Vallejo MAPU. This integrated approach has been used to analyze the spatial dynamics and transformation of MAPUs, recognizing their cultural and social value in the contemporary urban context.

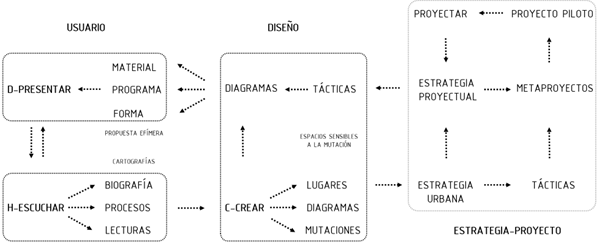

Source: Gamarra et al. 2022.

Figure 1. Outline of the Human-Centered Design (HCD) methodology adapted to the case study for new interventions in Chiclayo's MAPUs

The hodological approach is a methodology used in the study of paths and their influence on the organization of urban space. It recognizes that paths are not only physical elements but also have a deep cultural and social meaning. In the context of MAPUs, this approach has allowed us to understand how pre-Hispanic routes and paths continue to influence human behavior and the configuration of urban space today. Hodology has become a lens through which the layers of history and culture that overlap in these sites can be analyzed.

Fractal geometrization techniques have been used to analyze the structure and geometry of MAPUs. These techniques offer an in-depth understanding of the complexity and self-similarity of urban spaces, revealing underlying patterns in the layout of streets and buildings within MAPUs. The application of fractal measurements to these structures has made it possible to characterize their shape and spatial distribution, which has helped identify key areas for urban revitalization.

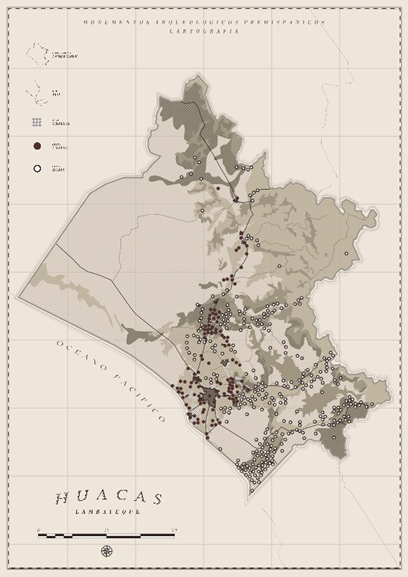

Source: Balarezo et al. 2022.

Figure 2. Mapping of pre-Hispanic archaeological monuments in the Lambayeque Region, differentiated by their geographical location in rural and urban areas

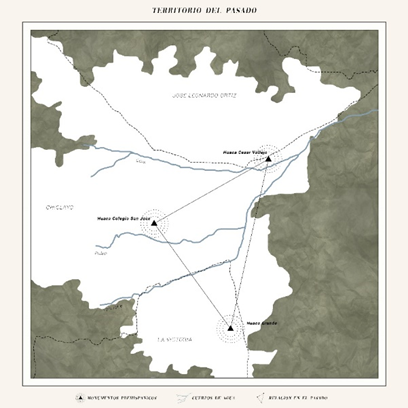

Source: Balarezo et al. 2022.

Figure 3. Triangulation of urban huacas in the three districts of Chiclayo, José Leonardo Ortiz, and La Victoria

In addition to fractal geometrization, spatial triangulations have been used to map the connectivity between traditional spaces in MAPUs and current socioeconomic, cultural, and ecological development opportunities. This technique has helped identify areas of convergence and divergence in the organization of urban space, highlighting critical areas for revitalization. Spatial triangulations have also revealed how MAPUs can serve as meeting points and places of inclusion for the population, promoting citizen participation and enjoyment of the city.

The project strategy developed in this research has been carried out in collaboration with experts in architecture and urban planning and with the active participation of the local community. The focus has been transforming inactive MAPUs into active hodological spaces by designing mixed-use and specific-use corridors. These corridors have been carefully planned to encourage continuity and diversity in street use, making the most of existing infrastructure and productive resources. This project strategy is essential for revitalizing MAPUs and their effective integration into contemporary urban life.

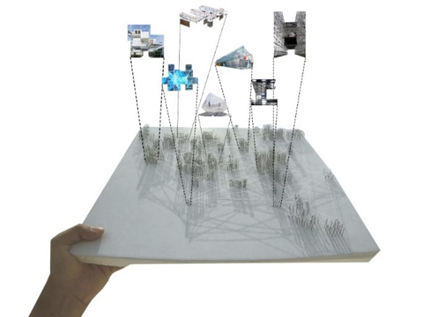

Source: Carrasco et al. 2022.

Figure 4. Model of project strategies in Chiclayo

A key component of this research has been implementing an imaginary pilot project in the César Vallejo MAPU. This project has been carried out as a strategic point of transformation for the city of Chiclayo. It has been based on the temporary collective use of space, considering the management of locally rooted projects with a global vision. The success of this pilot project demonstrates the viability and potential of the methodology used in this research.

RESULTS

Like many contemporary cities, Chiclayo's urban landscape is characterized by constant change and a fragmented vitality around its MAPUs, which has repercussions for its public spaces. Because instead of being places to stay, these spaces have become areas denied to daily activities or, failing that, areas of transition, reflecting the transition from a “solid” to a “liquid” modernity, as Bauman describes it in his work “Liquid Times”.(5) This “liquid city” is characterized by its flexibility and the need for individuals to adapt to new circumstances constantly.

In this context of constant change, research has focused on a new way of seeing the city as a constantly evolving landscape. Climatic phenomena have exposed the errors accumulated in the city's negative layers, opening up the possibility of seeking contemporary strategies to reactivate urban life in Chiclayo.

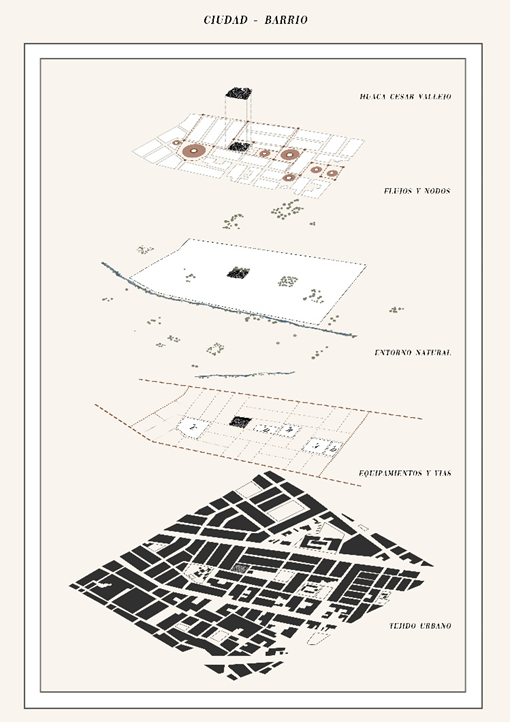

Source: Balarezo et al. 2022.

Figure 5. Projective readings of the urban fabric where the Huaca César Vallejo is located in José Leonardo Ortiz, Chiclayo

To address this situation, urban(6) and architectural enzymes have been proposed to act as catalysts for urban mutation. These enzymes become strategic points for the transformation of the city and the creation of new centralities. The aim is to reduce travel within the city, promoting movements of no more than five minutes by bicycle and 15 minutes on foot between neighborhoods. This not only reduces society's energy expenditure but also fosters connections between neighborhoods, leisure activities, and an open community.

The urban acupuncture strategy is fundamental to this process. Catalyst enzymes generate hybrid buildings in the city, reusing existing infrastructures and implementing new sustainable technologies and local ecologies. In addition, the wisdom of local farmers has been adopted, as they have learned to generate architecture from generation to generation in harmony with the territory. This involves engaging citizens in transforming their city, producing meanings and relationships that enrich urban life.

The research has put forward a comprehensive proposal integrating architecture with political, social, economic, and cultural aspects. A pilot project has been carried out at the MAPU Cesar Vallejo, focusing on areas of absence, in-between places, and spaces of presence. These spaces have been addressed with reversible interventions, multi-layered applications, and dematerialization to create ephemeral situations and enable the use of urban voids.

In this process, the right to the city, as proposed by Henri Lefebvre, has been respected. This seeks to enable citizens to regain control of the urban forms around them and participate in the creation of political spaces. Citizens have shown a strong impetus to improve the quality of life in Chiclayo, which has led to increased participation and collective action.

The research has addressed Chiclayo's contemporary urban challenges from a multidisciplinary perspective. It has proposed an urban transformation strategy that recognizes the city's flexibility and constant change, taking advantage of the catastrophe and the diversity of urban voids to create quality public spaces. This strategy involves citizens creating their urban environment and promoting a participatory urban planning approach. The research has laid the foundations for significant change in Chiclayo and offers valuable lessons for tackling similar challenges in other Latin American cities.

DISCUSSION

Chiclayo is a city oversaturated by urbanity, where it is necessary to arouse the interest of the government, promoted and supported by citizen groups, to apply strategies for the recovery and creation of spaces for public and/or collective use, where the possibility of coexistence and expression is offered to each citizen, thus generating a sense of belonging to the community and the neighborhood in which they live. As there are no large areas for growth within the city, specifically in the area of study, they are recognized as Clément(7) residual, abandoned spaces with opportunities full of potential.

Hernando Navarro(8) it points out that the obsolete or empty urban spaces that we find throughout the city are not only conditioned by crises but are also influenced and affected by time and, above all, by the unexpected changes that arise in the dynamics of the city. Therefore, public-private participation is considered necessary by the government with the establishment of intervention policies and/or incentives for the private sector to recover and use these spaces in favor of the city and its inhabitants. Rosero Muñoz(9) and Hernando Navarro(8) proposes the recovery of urban voids and the possibilities they offer as structuring elements that allow proposals to be articulated around them before considering building elsewhere.

Thus, as a result of fieldwork within the Monumental Zone of Chiclayo, a high percentage of urban voids were found to be valued as possible public spaces, which would give rise to a catalyzing -multiplying- effect as elements of urban revitalization, as argued by Rosero Muñoz(9). In turn, 91,70 % of urban voids have a medium to high relationship with the city, which can be reused and reintegrated into urban activities, activating the street and economic flow. These data are related to the ideas of Barajas(10), who argues that spaces understood as artificially constructed atmospheres can become platforms for the coexistence of different social and biological life forms and impact the links of collective everyday life in the urban imaginary.

The rescue - and generation - of public spaces through management and consultation shapes and establishes a strategy that achieves high levels of quality and revitalization in the city.(11,12,13) Therefore, it is considered essential that the authorities who encourage local development allow citizen participation when working in these spaces because empowering the identity of the inhabitants reduces the possibility of rejection by them,(14,15) thus giving rise to a shared vision, with alliances and agreements that evoke the co-responsibility of the population involved.(16)

The significance of public spaces is interpreted through the direct relationship between the perception of the inhabitants and their emotional relationship with the city they inhabit. In this respect, their deficit or scarcity affects people's standard of living.(17) Gehl(11) states that the quality of public space can be evaluated through the quality of the social ties it generates, its power to mix groups and behaviors, and its capacity to induce identity, expression, and cultural fusion. For this reason, it is ideal for public spaces to have specific formal characteristics such as continuity in these urban spaces, order, generosity, or liberality of form, design, materials, and elements.

The quality of public space is linked to the notion of capacity, the meaning of which alludes to the tangible probability of carrying out technically probable and socially desirable activities,(18) which is related to the characteristics and qualities of the space in use and even more so to the facilities that make up the functional support surface for the activities carried out and the interrelation of individuals.(19,20) In this way, space has a dual nature: it conditions and is conditioned by the individuals residing there.(21,22)

Finally, triangulated research between the academic field, architectural design, and citizen participation - human-centered design - considers it important to leave open the possibility of self-management, execution, and assembly of the meta-projects in a real context, with private financing or for the benefit of organizations with sustainable development objectives that can join in the activation of the city. Open-source interventions are only shown as enzymatic prototypes. However, they can take any desired form, move, and be located in several urban voids simultaneously without trying to imitate concepts used in other publications, as if they were deadly machines Reeve(12) on a domestic scale. For this reason, the aim should be to expand and improve the conditions and physical characteristics of the space, encouraging the integration of the urban circle. Providing the space with areas for interaction and coexistence will facilitate active and constant participation between the governing authorities and society.

CONCLUSIONS

The activation and recovery of urban pre-Hispanic Archaeological Monuments (MAPUs) play a crucial role in improving the conditions of public space and revitalizing the city. These spaces can become meeting and inclusion points for the population, thus promoting citizen participation and enjoyment of the city.

It is essential to develop policies that promote the creation of an interconnected system of public spaces, taking urban MAPUs as a starting point and using them to generate the city's structuring elements. This can boost urban renewal processes and contribute to the vitality and dynamism of the city and its inhabitants.

The new public spaces should be conceived as adaptable, innovative, and resilient, recognizing that the city is in constant transformation. The openness, heterogeneity, and accessibility of these spaces must be priorities, and this can be achieved through collaboration with the authorities and the active participation of the community.

Activating MAPUs through activities of public interest can generate new functional, social, and economic dynamics that meet citizens' needs. This supports the right to the city and promotes urban life through encounters, movements, improvisation, and opportunities.

Through enzymatic and tactical approaches, the city can become a stage for the spontaneous, where urban MAPUs are transformed into spaces of possibility. The community's recovery and appropriation of these MAPUs improve the quality of urban life and foster a sense of belonging to the city on the part of its inhabitants.

The integral approach that combines hodology, fractal geometrization, spatial triangulations, project strategy, and the implementation of an imaginary pilot project to understand and revitalize the Urban Pre-Hispanic Archaeological Monuments in Chiclayo is shown to be a methodology that recognizes the cultural and social importance of these sites, where working together with the local community allows for a significant transformation in the city so much so that this interdisciplinary approach provides a solid foundation for future research in urban revitalization and Hodologies and offers a roadmap for the recovery of endangered historical sites around the world.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

1. Careri F. Walkscapes: El andar como práctica estética. Gustavo Gili. 2014.

2. Lefebvre H. La revolución urbana. Alianza. 1972.

3. Augé M. Los no lugares. Espacios del anonimato. Una antropología de la sobremodernidad. Gedisa. 2008.

4. Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, F. S. Chapin I, Lambin E et al. Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society. 2009; 14(02):32. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss2/art32/

5. Bauman Z. Tiempos líquidos: vivir en una época de incertidumbre. Tusquets. 2008.

6. Ibañez D, Rubio R. Multicuerpo de catalizadores urbanos. Arquitectos: información del Consejo Superior de los Colegios de Arquitectos de España. 2006;179:93-95.

7. Clément G. Manifiesto del tercer paisaje. Gustavo Gili. 2018.

8. Hernando Navarro E. La recuperación de vacíos urbanos y su transformación en nuevos espacios productivos. La experiencia del proyecto BETAHAUS en Berlín y Barcelona. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. 2013.

9. Rosero Muñoz L. Vacíos urbanos piezas estructuradoras de ciudad. 2017.

10. Barajas D. A Study of Global Mobility and the Dynamics of a Fictional Urbanism. Episode Publishers. 2013.

11. Gehl J. Ciudades para la gente. Ediciones infinito. 2014.

12. Reeve P. Máquinas Mortales. Alfaguara. 2017.

13. Ábalos I, Sentkiewicz R. Campos prototipológicos termodinámicos. Mairea. 2011.

14. Berger J. Modos de ver. Gustavo Gili. 2019.

15. Careri F. Artes cívicas. En Pasear, detenerse. Gustavo Gili. 2016.

16. Davis R. Huacas of Lima. University of California Press. 2006.

17. Duarte C, Alonso S, Benito G, Dachs J, Montes C, Pardo Buendía M et al. Cambio global: Impacto de la actividad humana sobre el sistema Tierra. CSIC. Consejo Superior de Investigaciones científicas. 2006.

18. García Vázquez C. Teorías e historia de la ciudad contemporánea. Gustavo Gili. 2016.

19. Gómez-Sal A, Belmontes JA, Nicolau, JM. Assessing landscape values: a proposal for a multidimensional conceptual model. Ecological Modelling. 2003; 168(3):319-341.

20. Green D. De la pobreza al poder: cómo pueden cambiar el mundo ciudadanos activos y estados eficaces. Intermón Oxfam. 2008.

21. Lefebvre H. El derecho a la ciudad (3o). Península. 1975.

22. Tapia García C, Rodrigue M. Townscapes/Townscopes: del Paisaje Monumental al Hodológico. 2016.

FINANCING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio, Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén, Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo.

Data curation: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio, Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén, Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo.

Formal analysis: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio, Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén, Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo.

Drafting - original draft: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio, Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén, Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo.

Writing - proofreading and editing: Jorge Carlos Carrasco Aparicio, Manuel Agustín Gamarra Sampén, Oscar Víctor Martín Vargas Chozo.